A product design position at Stripe receives approximately 2,500 applications per opening. The hiring team reviews each portfolio for an average of three minutes before deciding whether to advance the candidate.

In those three minutes, your portfolio must communicate not just what you've designed but how you think, solve problems, and collaborate with others. The designers who land these competitive positions understand that portfolios are not galleries of finished work—they're demonstrations of professional capability presented through carefully constructed narratives.

This reality explains why talented designers with impressive project histories often struggle to get interviews while less experienced designers with strategically constructed portfolios advance to final rounds.

The difference lies not in design skill but in portfolio communication effectiveness. Understanding what hiring managers actually evaluate—and building your portfolio to address those criteria directly—dramatically improves interview rates regardless of experience level.

Conversations with design hiring managers at companies including Google, Airbnb, Figma, and numerous startups reveal consistent evaluation patterns that informed designers can address explicitly. This guide examines those patterns and provides a framework for building portfolios that perform in competitive hiring environments.

What Hiring Managers Actually Evaluate

The most common portfolio mistake is treating hiring managers as design critics who will evaluate visual aesthetics and award jobs to the most beautiful work. In reality, hiring managers evaluate portfolios primarily as evidence of working capability.

They're trying to answer specific questions: Can this person identify real problems? Do they understand users? Can they work through constraints and ambiguity? Will they communicate effectively with stakeholders? Beautiful final designs matter less than clear demonstration of these professional competencies.

Process documentation has become the most important portfolio element because it directly addresses the questions hiring managers need answered. A case study showing research findings, design iterations, and stakeholder feedback demonstrates problem-solving capability in ways that final mockups cannot.

Hiring managers consistently report that they skip portfolios containing only final designs without process context—there's simply not enough information to evaluate the candidate's working ability.

The ability to articulate design decisions carries significant weight because design work is inherently collaborative. Designers present to stakeholders, negotiate with engineers, and explain rationale to cross-functional partners daily.

A portfolio that clearly explains why specific design choices were made—not just what those choices were—demonstrates communication capability that predicts job performance. Conversely, portfolios that present work without explanation suggest candidates may struggle to advocate for their designs in professional contexts.

Relevance to the target role matters more than portfolio breadth. A product designer position requires evidence of product design capability; an agency role requires demonstrated versatility across client types.

Including every project you've ever completed dilutes focus and forces hiring managers to hunt for relevant evidence. The most effective portfolios feature three to five projects deeply relevant to the target position, presented with enough depth to demonstrate qualified expertise in that specific domain.

Case Study Architecture That Demonstrates Capability

Case studies separate portfolios that generate interviews from those that don't. The structure of these presentations determines whether hiring managers can extract the information they need to evaluate candidates favorably.

Effective case studies open with context that orients readers unfamiliar with the project or company. This framing should establish the business situation, your specific role, the timeline, and the team composition. Without this context, hiring managers cannot accurately evaluate the scope and constraints of your work.

A project that seems simple might actually involve significant complexity; a seemingly impressive result might reflect favorable circumstances rather than exceptional skill. Providing context enables accurate assessment.

Problem definition demonstrates analytical capability that hiring managers value highly. Articulating what wasn't working, why it mattered, and what constraints existed shows that you can identify problems worth solving—a skill that precedes any actual design work.

The best problem definitions include specific evidence: user research findings, analytics showing drop-off points, stakeholder feedback indicating pain. This evidence-based framing signals a professional approach to design rather than aesthetic preference-driven decision making.

The process section provides the evidence hiring managers need to evaluate your working capability. This section should show how you moved from problem to solution, including the dead ends, iterations, and pivots that characterize real design work. Wireframes, prototypes at various fidelity levels, user testing results, and design critiques all belong here. The narrative should explain not just what you did but why—what each activity aimed to discover or validate and how findings informed subsequent decisions.

Outcomes and reflection complete the case study by demonstrating impact awareness and growth orientation. Quantified results strengthen cases significantly: metrics improvements, user feedback, business outcomes. When quantified results aren't available, qualitative outcomes like stakeholder reception, user feedback quotes, or successful launch can substitute. The reflection component—discussing what you learned and what you'd do differently—demonstrates self-awareness and continuous improvement mindset, qualities managers consistently value.

Strategic Project Selection

What you choose to include matters as much as how you present it. Strategic project selection maximizes the signal hiring managers receive about your capability while minimizing noise that distracts or confuses.

Lead with your strongest, most relevant project. Portfolio analytics consistently show that most visitors view only one or two case studies before deciding whether to proceed or move on. If your best work is buried in position four or five, many evaluators will never see it. Additionally, first impressions anchor subsequent evaluation—a strong opening case study creates favorable context for interpreting later projects, while a weak opener creates skepticism that colors everything that follows.

Recency signals current capability level. Work from three or more years ago likely reflects outdated skills, tools, and design sensibilities. Even if older projects represent your most impressive work, their age raises questions about whether you've maintained that level of performance. When older work is significantly stronger than recent projects, consider updating the presentation—new case study writing, refreshed visuals, current reflection—to demonstrate that you've continued learning even if the core work is dated.

Coherent focus typically outperforms eclectic variety. A portfolio containing a mobile app, a brand identity system, an illustration project, and a VR experience might suggest versatility, but it more often reads as unfocused. Hiring managers struggle to categorize candidates with diverse portfolios, making them harder to advocate for in hiring discussions. Portfolios focused on a specific domain—enterprise SaaS, consumer mobile, e-commerce—tell a clearer capability story and position candidates as specialists rather than generalists.

The rare exception to this guidance involves candidates genuinely pursuing roles that value versatility, such as design agency positions or early-stage startup roles where wearing multiple hats is expected. In these cases, variety becomes a feature rather than a bug, though projects should still be individually excellent rather than representing dabbling in multiple domains.

Technical Execution and Platform Decisions

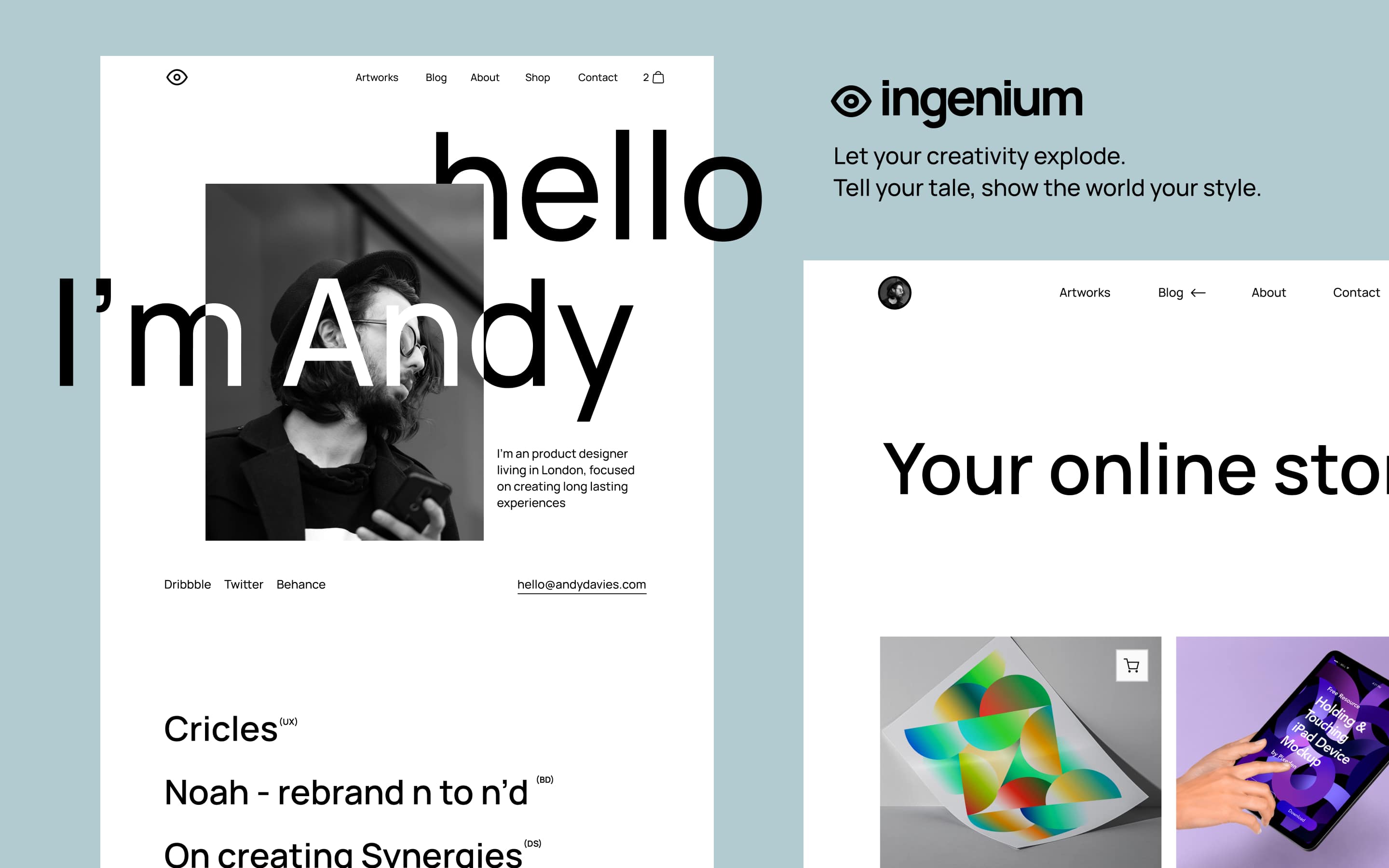

The portfolio website itself functions as an additional portfolio piece, demonstrating your attention to detail, technical capability, and aesthetic sensibility. This meta-level evaluation means that technical quality matters beyond mere functionality.

Performance affects perception significantly. Slow-loading pages suggest carelessness or limited technical capability—neither impression helps candidates. Image optimization, efficient code, and appropriate hosting ensure pages load quickly across connection speeds.

Testing across devices and browsers reveals issues that might otherwise surface only when a hiring manager views your portfolio on their particular setup. The few hours required to optimize performance prevent negative impressions that can disqualify otherwise strong candidates.

Mobile responsiveness is non-negotiable. Hiring managers review portfolios on various devices at various times—during commutes, between meetings, lying in bed. A portfolio that breaks on mobile tells hiring managers you don't test your work thoroughly or don't consider users on different devices. Given that responsive design is a fundamental skill for modern product designers, a non-responsive portfolio actively contradicts capability claims.

Platform selection involves tradeoffs between control and efficiency. Building a custom portfolio from scratch demonstrates technical capability and allows complete design control, but requires ongoing maintenance and typically takes longer to create.

Template-based platforms like Webflow, Squarespace, or Framer provide professional results quickly with less effort, though customization has limits. The right choice depends on your circumstances: candidates emphasizing technical skills might benefit from custom builds, while those prioritizing content over implementation can leverage templates effectively.

Regardless of platform, certain portfolio elements require presence and prominence. Clear navigation to major sections (projects, about, contact) should be immediately obvious. Contact information should be accessible without hunting. Project thumbnails should communicate content clearly even before clicking through. An about page should humanize you with background, design philosophy, and current focus. These elements constitute baseline expectations that missing or poorly-implemented instances count against candidates.

Distribution and Maintenance

A strong portfolio requires viewers to generate value. Strategic distribution increases the likelihood of reaching relevant decision-makers while maintenance ensures your portfolio continues performing over time.

Application integration is the primary distribution channel. When applying to positions, include your portfolio link prominently—in the application itself, on your resume, in your cover letter. Assume that links buried in application forms may be overlooked; placing the URL in multiple locations increases the chance of it being found. When applications allow file uploads, consider including key case study pages as PDFs alongside portfolio links, ensuring reviewers can access your work even if link following is inconvenient.

LinkedIn serves as a discovery platform where many hiring processes begin. Your headline should include "Product Designer" or equivalent role title for searchability, and the URL to your portfolio should appear in your profile summary and experience descriptions. When recruiters search for designers, your profile should make the path to your portfolio obvious. Similarly, designer-focused communities like Dribbble, Behance, and design Twitter/X provide visibility that sometimes generates inbound interest, particularly when you actively participate in these communities rather than merely posting work.

Maintenance prevents portfolio decay that undermines otherwise strong presentations. External links break over time; companies get acquired and URLs change. Quarterly link verification prevents embarrassing dead ends. Project relevance shifts as your career progresses and target roles evolve—removing or de-emphasizing outdated work keeps your portfolio focused on current aspirations. Analytics, if installed, reveal which projects receive attention and where visitors drop off, informing refinements that improve performance.

The designers who consistently land interviews at competitive companies treat their portfolios as ongoing projects rather than one-time creations. They update with new work, refine based on feedback, and adapt to changing career goals. This maintenance investment compounds over time, creating portfolios that improve with each iteration while unmaintained portfolios gradually become liabilities.